Birth House (Mammisi) Birth House (Mammisi) |

| . |

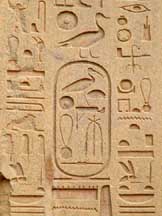

Cartouche |

| . |

Cavetto

cornice / Egyptian cornice |

| . |

| Chevron |

| . |

Colonnade Colonnade |

| . |

Columns, Egyptian |

| . |

Cornice

See Cavetto cornice / Egyptian cornice |

| . |

|

Hieroglyphics

Ancient system of writing based on symbols or pictures to

denote objects, concepts, or sounds, originally and especially in the writing system

of ancient Egypt.

Egyptian hieroglyphs decoded in 1882 (Wikipedia:

Rosetta Stone).

Cartouche:

an oblong, or oval, magical rope which was drawn to contain the ancient Egyptian

hieroglyphics that spelled out the name of a King or Queen.

|

The decoration of temple

walls consisted largely of representations of acts of adoration of the monarch to

his gods, to whom he ascribed all his success in war. The Egyptians, masters in the

use of colour, carried out their schemes of decoration chiefly in blue, red, and

yellow. The wall to be decorated was probably prepared as follows: The decoration of temple

walls consisted largely of representations of acts of adoration of the monarch to

his gods, to whom he ascribed all his success in war. The Egyptians, masters in the

use of colour, carried out their schemes of decoration chiefly in blue, red, and

yellow. The wall to be decorated was probably prepared as follows:

(a) the surface was first chiselled smooth and rubbed down;

(b) the figures or hieroglyphics

were then drawn with a red line by an artist and corrected with a black line by the

chief artist;

(c) the sculptor made his carvings in low relief [bas-relief]

or incised

the outline, slightly rounding the enclosed form towards its boundaries;

(d) a thin skin of stucco was probably applied to receive

the colour, and the painter carried out his work in thestrong hues of the primary

colours.

The hieroglyphics were sometimes incised direct on the stone

or granite and then coloured...

The Egyptians possessed great power of conventionalising

natural objects and they took the lotus, palm, and papyrus as motifs for design. These were nature symbols of the fertility

given to the country by the overflowing Nile, and as such they continually appear

both in construction and ornament.

- A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method,

by Sir Banister-Fletcher, New York, 1950, pp. 41-42

|

|

| . |

|

Houses Houses

The

wealthy lived in palaces or villas; the the general population lived in row houses

built of sun-dried mud bricks. Huts were made of reeds with inward sloping (battered)

walls and thick bases to resist the annual Nile inundation.

Evidence for what ordinary houses were like in ancient Egypt is gotten by

looking at model houses that have been found buried in tombs and by surviving Egyptian

houses built in the traditional way. Both were constructed of bricks, shaped in a

wooden mold, made of chopped straw mixed with sun-dried mud from the Nile banks covered

over with a thin layer of plaster. Both were built to a simple, square design, with

a flat roof, sometimes topped by a terrace where the inhabitants could sit and enjoy

the cool, fresh, evening air. Inside, the rooms were small and dark, with narrow

windows and low ceilings. Some houses had two storeys; others were all on one level.

Many had cellars for storage, dug into the rough ground underneath.

Most people lived in villages, clustered along the banks of the River Nile. Village

houses were built close together, for strength and security. The villages were surrounded

by ditches and fields. Nearby, was the bleak, endless desert, for the Egyptians this

was the home of the dead.

|

| . |

|

Hypostyle Hypostyle

(HIGH pa stile)

Covered colonnade (a row of evenly spaced columns,

usually supporting a roof or a set of arches.)

Hypostyle hall:

"Large room with a flat roof carried on massive columns close-set in rows,

the middle rows often having taller columns to accommodate a clearstory." -

James

Stevens Curl, The Egyptian Revival: Glossary - Hypostyle, p. 441

|

| . |

Lotus Lotus |

| . |

Mythology |

| . |

Narmer

In 3000 B.C.., King Narmer of upper Egypt defeated the

ruler of Lower Egypt and established the first political dynasty to rule one unified

country. |

| . |

Obelisk |

| . |

|

Ornament

|

Ornament Ornament

The decoration

of temple walls consisted largely of representations of acts of adoration of the

monarch to his gods, to whom he ascribed all his success in war. The Egyptians, masters

in the use of colour, carried out their schemes of decoration chiefly in blue, red,

and yellow. The wall to be decorated was probably prepared as follows:

(a) the surface was first chiselled smooth and rubbed down;

(b) the figures or hieroglyphics were then drawn with a red line by an artist and corrected with

a black line by the chief artist;

(c) the sculptor made his carvings in low relief or incised the outline, slightly rounding the enclosed form towards its boundaries;

(d) a thin skin of stucco was probably applied to receive

the colour, and the painter carried out his work in thestrong hues of the primary

colours.

The hieroglyphics were sometimes incised direct on the stone

or granite and then coloured...

The Egyptians possessed great power of conventionalising

natural objects and they took the lotus

, palm, and papyrus as motifs for design. These were nature symbols of the fertility

given to the country by the overflowing Nile, and as such they continually appear

both in construction and ornament.

- A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method,

by Sir Banister-Fletcher, New York, 1950, pp. 41-42; Drawings: p. 42

|

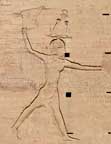

- Illustration - Pharaoh Ptolomy XII in a

victory pose: Edfu

|

| . |

Palm (palmette) |

| . |

Papyrus

plant |

| . |

|

Ptolemaic dynasty

|

Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt

during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30

BC.

Ptolemy, a somatophylax, one of the seven bodyguards who

served as Alexander the Great's generals and deputies, was appointed satrap of Egypt

after Alexander's death in 323 BC. In 305 BC, he declared himself King Ptolemy I...

The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors

to the pharaohs of independent Egypt. Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman

conquest of 30 BC.

All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy.

Ptolemaic queens, some of whom were the sisters of their husbands, were usually called

Cleopatra, Arsinoe or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen,

Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar

and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her suicide at the conquest

by Rome marked the end of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt.

|

See also: Pharaohs

|

| . |

|

Pylons Pylons

Monumental gateway to an Egyptian temple, consisting

of a pair of tower structures with battered walls flanking the entrance portal.

Two tapering towers, each surmounted by a cornice, joined by a less elevated section which enclosed the entrance between

them.

Supposed to represent the akhet (horizon) hieroglyph.

Pylons are the largest part of the temple and were mostly built last.

Steeply battered

pylons resisted earthquake shocks.

Torus mouldings along the edges,

essentially recreate in stone the bundles used to strengthen the corners of the reed

originals. The vegetal motif also appears in the cavetto

cornice at the top of the walls, the curve of which replicates the drooping heads

of the plants that had been woven together as mats.

See also: Karnak

Temple Complex, Egypt: Pylons

|

| . |

|

Pyramid Pyramid

First pyramid was a step pyramid built in 2650 B.C. The steps represent a gigantic

stairway for the king to climb to join the sun-god in the sky.

Later King Sneferu's pyramid had sloping sides, the intent being to recreate the

mound that had emerged emerged out of the watery ground at the beginning of time.

The largest pyramid is the Great

Pyramid at Giza, built for King Khufu (Cheops) in c.2589

B.C.

|

| . |

|

Ramses II (Ramesses / Rameses) Ramses II (Ramesses / Rameses)

Third Egyptian pharaoh of the Nineteenth dynasty. He was

born around 1303 BC and at age fourteen, Ramesses was appointed Prince Regent by

his father Seti I. He is believed to have taken the throne in his early 20s and to

have ruled Egypt from 1279 BC to 1213 BC for a total of 66 years and 2 months

He built more monuments and set up more statues than any

other pharaoh.

Statues:

|

| . |

Relief |

| . |

Roll molding

Any convex, rounded molding, which has (wholly or in part)

a cylindrical form; a plain round molding |

| . |

Sphinx |

| . |

|

Temples Temples

During the New Kingdom Period in Egypt, roughly the latter half of the second

millennium BC, there were two principal types of temple:

1. Cult temples, dedicated to the worship of the gods of Egypt - Amun,

Ptah, Horus, Osiris, etc., and were designed to accommodate their images

2. Mortuary temples dedicated to the worship of the deified pharaoh.

Cult temples followed a tripartite plan, consisting of three basic elements: an

outer court; a hypostyle (or columned) hall; and the sanctuary itself. common addition

was an enormous gateway known as a pylon at the entrance of each courtyard,

The ancient Egyptians believed that the world began with the emergence of the

Primeval Mound from the watery abyss. The sanctuary represented the mound of creation

and was higher than the rest of the temple. The columns of the Hypostyle Hall were

carved in the shape of lotuses, lilies and papyrus plants, a reproduction of the

marshes surrounding it. Each year the god left the sanctuary, to travel through the

streets of the city and visit the other gods. In this procession, he was carried

in sacred boat on the shoulders of his priests, gliding through the sacred swamp

to receive the adoration of his worshippers.

|

| . |

Torus Torus |

| . |

|

Walls

|

Temple walls were immensely thick, of limestone, sandstone,

or more rarely of granite. The wall faces slope inwards or batter

externally towards the top, giving a massive appearance. Authorities trace the origin

of this inclination either to the employment of mud for walls of early buildings

or because this form of wall was better able to resist earthquakes. Temple walls were immensely thick, of limestone, sandstone,

or more rarely of granite. The wall faces slope inwards or batter

externally towards the top, giving a massive appearance. Authorities trace the origin

of this inclination either to the employment of mud for walls of early buildings

or because this form of wall was better able to resist earthquakes.

Columns, which

are the leading external features of Greek architecture, are not used externally

in Egyptian buildings, which normally have a massive blank wall crowned with the

characteristic "gorge"

cornice of roll and hollow moulding.

Walls, even when of granite, were generally carved in low relief, sometimes coated

with a thin skin of stucco, about the thickness of a sheet of paper, to receive the

colour. Simplicity, solidity, and grandeur, obtained by broad masses of unbroken

walling, are the chief characteristics of the style.

- A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method,

by Sir Banister-Fletcher, New York, 1950, pp. 41-42; Drawings: p. 41

|

|

Birth House (Mammisi)

Birth House (Mammisi)

Colonnade

Colonnade

Lotus

Lotus

Torus

Torus