![]()

Shea's

Buffalo Theatre - Table of Contents

Reprint

The Majesty of Shea’s Performing Arts Center: What You've Never Known Before Employees

share

stories of their love for the historic downtown theater

March

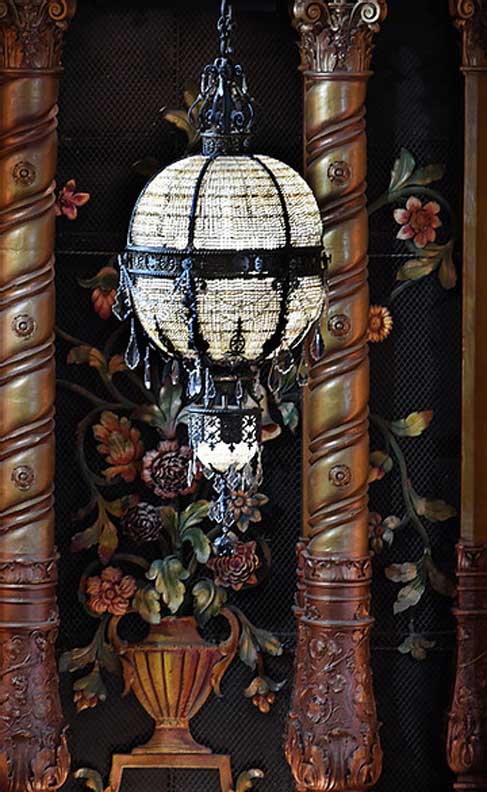

11, 2021: Doris

Collins examines a wall sconce located in a box seat. ©

photo by Steven

D. Desmond

Anyone who has ever visited Shea’s Performing Arts Center in downtown Buffalo’s Theatre District is struck by its majesty. Restoration over the last several decades has helped restore the theater to its past glory. A casual observer may not know the history behind Shea’s. Michael Shea, for whom the venue is named, was born in St. Catharines, Ontario, in 1859. Around the turn of the century, he operated several vaudeville theaters in Buffalo and Toronto. By the early 1920s, Shea and his associates had traveled the country to gather ideas for constructing an ornate theater in Buffalo. Cornelius and George Rapp, famous theater architects based in Chicago, were hired to design a building that would resemble a European opera house and “compare favorably with such buildings in other cities.” The initial plan was to spend approximately $1 million, but investors eventually spent twice that. First opened to the public in 1926, the property underwent several changes in ownership, as American culture evolved over time. By the mid-1970s, Shea’s had fallen into disrepair and plans were underway to strip the theater’s interior before tearing down the building. The City of Buffalo assumed ownership during foreclosure. Citizens banded together to form Friends of the Buffalo Theatre, Inc. The group managed the theater for several years. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.  ©

photo by Steven D. Desmond

Public and private funding through the 1980s and 90s helped

stabilize

the theater’s outlook. Over the years, dressing rooms and the

stage

have been expanded. (At 5000 square feet, Shea’s stage is one

of the

largest in North America.) Other projects included rewiring

the

building, replacing seats and draperies, and restoration of

facades and

marquees on Main and Pearl Streets. In modern times, Shea’s

hosts

traveling Broadway shows and concerts.People who work there recognize the history of the grand old venue, and their day-to-day responsibilities allow them to experience behind-the-scenes moments that patrons simply don’t see. “We sometimes take for granted the beauty of the building and the facility,” said Bobbi Scott, who has worked in hospitality for more than two decades. “You walk in and breathe it. With the history, it’s such a unique and different place to work. People who come to see a show don’t always observe the dedication to keeping the building restored and operating it.” “It’s hard not to get addicted to this place,” said Doris Collins, who has worked as the Historic Restoration Consultant for the past 25 years. “The sheer beauty is something the average citizen doesn’t always see. Our theater is from a bygone era. The wrecking ball was here three times, but citizens banded together to see it put on the National Registry.” Optical illusions are plenty. The ceiling inside the theater appears to be decorated with hand-carved wood, but is actually molded plaster. The pillars, which resemble marble, are scagliola, an imitation marble made of plaster that is mixed with glue and dyes. The gypsum plaster was handcrafted in Buffalo. Maintaining a working theater requires a team of professionals, all of whom have a story. Restoration Consulting “My job is to bring back any interior sections of the building that have been changed or damaged,” Collins explained. “Restoration does not mean renovation. You put things back the way they once were to the best of your ability. It’s okay to substitute materials.” Collins, 75, was born in Germany, and her family relocated to the United States when she was 10. She worked as an art teacher, and became interested in restorations while living in Northern Italy and working in Austria. Later, while employed by a decorating firm in Erie, Pennsylvania, she met a contractor who requested help framing artwork from churches. This experience led her to a restoration job at Our Lady of Victory Basilica in Lackawanna. There, she met Tony Conte, a board member at Shea’s, who invited her to oversee the theater’s restoration. Since the mid-1990s, Collins has guided a team of dedicated volunteers who are committed to preserving and restoring Shea’s to its past glory. “If there are problems, we find the cause and put patches in,” she said. "It’s usually water damage. I teach people how to determine what the damage is, and how to repair it. We accept volunteers with no experience. You have to love what we do and be willing to take instruction. It’s not brain surgery.”  © photo by Steven D. Desmond “The designer was consistent with a color palette,” she noted. “I was constantly stripping a couple square inches and seeing what was underneath.” From a bygone era, the theater allowed smoking in the lobby. Decades of that left a thin layer of dirt and grime on everything. “You can clean that,” Collins said, “but you take off a little paint every time you do.” Shea’s employees recognize that the theater is a working space, and they try to be accommodating to traveling performers and their crews. Although Collins has observed celebrities like Carol Channing, Theodore Bikel, and Gloria Estefan, she does not go backstage unless she’s invited. “Broadway touring shows rent the space. They don’t expect visitors to come through. They’re here to work, not chitchat, so we try not to disturb them.” Collins recalled a memorable visit by Marie Osmond, who performed in The Sound of Music during 1994, a few weeks before Christmas. “She needed to do some holiday shopping and asked if one of our staff would drive her to a nearby store,” Collins said. “She stood in line at the Galleria Mall. When she was ready to make her purchases, other shoppers recognized her and offered to let her go to the head of the line, which she graciously declined. Instead of talking about herself, she encouraged people to come see the show in one of the finest theaters in the country. She was absolutely in awe of Shea’s.”  From

one of the box seats, a view of Shea's interior

that most patrons don't see. © photo by Steven D.

Desmond

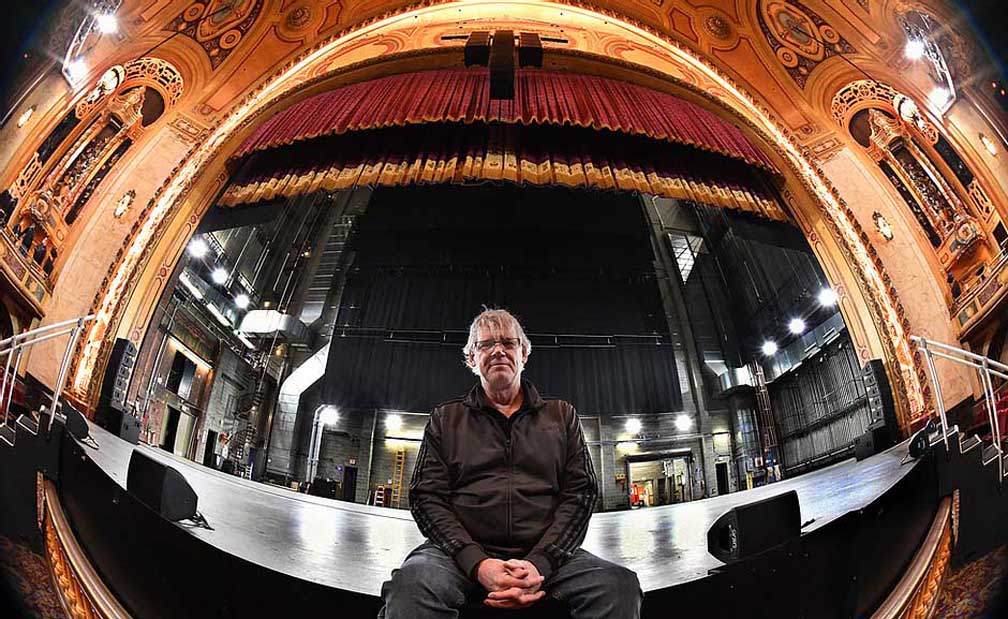

‘In case you’re wondering, I’m James Taylor…’ While Collins focuses on restoration, Bill Hedrick has a different perspective. He is the theater’s senior production manager. “I’m the guy backstage,” he explained. “I get shows up and running.” The job involves coordinating between stage labor, wardrobe and musicians. Since 2003, Hedrick has communicated with artists and production crews for each performance. “Anything they need to make their show go, I acquire and put together so that they’re ready when it’s 7:30 on the night the curtain goes up. It’s like being a plant manager in a factory and making sure everything works. The other part is serving as a concierge. I host people who are guests in our building for a day or sometimes weeks at a time. My job is to make them feel comfortable.” The job entails long hours. On the day of a show, he might be on site to meet a caterer at 6 a.m. In the hours after a show ends, Hedrick may finally close up at 2 a.m., 20 hours later. If there are back-to-back concerts, rather than go home for an hour or two, he uses a shower in the dressing rooms and sleeps on a cot in his office.  Bill

Hedrick sits at the

edge of one of the largest stages in North America. ©

photo by Steven

D. Desmond

Unlike Collins, he interacts with performers, and has many funny stories from his time on the job. One of his favorites involves singer James Taylor. “When James Taylor came through, it was billed as a one-man show,” Hedrick recalled. “They decided to have a day of rehearsal before the performance, so we loaded them in and got them set up and had the sets ready.” Once that was complete, Hedrick retreated to his office behind the organ pipes. With the door open, he heard a “boom boom crash” sound that played briefly, then stopped. Shortly, the sound was repeated. “Sometimes musicians check their rhythm tracks,” Hedrick said. “It’s not unusual.” But the “boom boom crash” was repeated several more times, with a healthy pause between each. This went on longer than expected. Eventually, Hedrick’s curiosity was peaked. “I walked out, and there was a huge mechanical device at the rear of the stage. Two guys in flight suits and hats are tinkering around with a machine that had levers and pulleys and drums. The best way to describe it was like an oversized music box with bumps and ridges that turned. One would hit a mallet that would then hit a bass drum. Another hit the snare. These guys were making adjustments to bumps on the wheel.” Hedrick stepped onstage and asked about the device. The taller man explained it was a mechanical drum machine. The other man said they had been assembling it in his garage, and this was the first time they planned to debut it for a show. Hedrick nodded. He had been expecting to hear James Taylor’s smooth singing voice at rehearsal, but instead these two stagehands were tinkering with a strange device. “I wonder what James thinks of this,” Hedrick mused. The taller man said, “I like it very much.” Hedrick was taken aback. Under the hat and flight suit, Taylor was here setting up. He grinned, explaining that the other man was his neighbor. They had been assembling the drum machine in the neighbor’s garage. “The whole time I was talking to the guy in the hat, I didn’t recognize him,” Hedrick admitted. Taylor ribbed Hedrick for the remainder of his time in Buffalo. “I was sitting with my people before the show, and James Taylor came in, sat down, looked right at me and said, ‘Hi, by the way, I’m James Taylor.’ Everyone started laughing. Each time he saw me, he’d say, ‘Just in case you’re wondering, Bill, I’m James Taylor.’ At the end he thanked me for our hospitality and being able to joke around. He was a great guy. And the drum machine worked fine.”  Shadows

reflect

interesting patterns from this lobby chandelier. © photo

by Steven D.

Desmond

Problem solving on the fly “Working in an old building does not come without its challenges,” said Bobbi Scott. As the Manager of Events and Hospitality, she has worked at Shea’s for 23 years. “I oversee the lobby with bars and concessions and bartenders,” she explained. “We also book all non-theatrical events, like weddings or meetings or corporate events.” Scott recalled an indoor wedding ceremony many years ago on a rainy afternoon when things inadvertently went awry. “It was one of those summer storms where rain started coming down really hard, to the point where water was gushing down Main and Pearl Streets and toilets were bubbling up. I was behind the scenes when it hit our grid, and the entire power system went out during the ceremony.” The sudden outage interrupted a grandfather’s blessing, shorting out his microphone. Scott said the couple being married and their guests were gracious and understanding. “Our stage house has a different power source, so we were able to run extension cords from there,” Scott recalled. “Also, we had a generator which provided a little power. The caterer was cooking in the stage house, so it didn’t affect that. We brought out candles and I had a boom box for music. It teaches you as an event planner that you always need extra stuff. It teaches you to be ready for the unexpected.”  Bobbi

in the lobby: Bobbi

Scott, Manager of Events and Hospitality,

appreciates the beauty of Shea's. © photo by Steven D.

Desmond

Rumors have circulated for years that Shea’s is haunted. At one time, ghost tours were given in the theater. In 2007, Sara Hood of North Tonawanda, a restoration volunteer, was interviewed on camera recounting her experience with a ghost who resembled Michael Shea. Shea’s portrait in the lobby is a talking point. “Whenever you walk by Michael Shea’s portrait, it’s almost always tilted,” Scott said. “Why is it not straight?” Like many Shea’s employees who log late nights and early mornings, Scott has spent overnights in the building. She has heard unexplained noises, but never felt frightened. “I’ve had little things happen,” she said. “One time we had a performance at the (adjacent) Smith Theater. Now it’s all connected, but at the time, you had to go outside to get from one place to the other. “I had to run back to Shea’s to get something from the bar, and it was easier for me to go through the back door. The back door of Smith comes to the stage door of Shea’s. I was running, and I heard a howl. It wasn’t an obvious ghost sound, but I was in a hurry, and thought, ‘I’m going to ignore that.’” After returning later, Scott understood that the sound emanated from a motor lift on stage. “No one was there, so I don’t know why it was running,” she said. “It was a little bit of a letdown.” ‘Do your worst!’ It isn’t just employees who’ve encountered ghost tales. Visiting performers have as well. “American Idol winner Taylor Hicks starred as Teen Angel during a run of Grease,” recalled Hedrick, the senior production manager. The touring company spent time at Shea’s in 2009.  One

of the most interesting

spots in Shea's, according to Doris

Collins, is a curved wooden door that serves as entrance

from the house

to the stage. © photo by Steven D. Desmond

“Taylor and his manager had been collecting stories

and taking pictures of every old theater they’d played during

the tour.

They asked if Shea’s had any ghosts.”Hedrick joked that he often spent overnights at the theater and was on good terms with the ghosts. Hicks asked if he could poke around and photograph the venue. Following the opening night party, Hicks, his manager, and Hedrick walked through the theater en route to the dressing room. “We headed through the lobby and entered the house, traveling down the Pearl Street aisle toward the pass through,” Hedrick recalled. “When we reached the lower right box, Taylor said, ‘This is a really cool theater, but it doesn’t feel as creepy as some of the others we’ve been to.’” Hedrick agreed that the ghosts might not be spooky, but were often dramatic. “We’re not afraid of you, ghosts,” Hicks shouted. “Do your worst!” At that moment, a loud click echoed through the empty theater. All the houselights went out. Only exit lights remained lit. “We stared at each other in shock for a moment. Then Taylor’s guy said, ‘Now look what you’ve done,’” Hedrick recalled. The three began laughing. Hedrick explained that the house lights were set on a timer, and they just happened to be standing there when the timer clicked off. “Or were we?” Hedrick wondered. “The rest of the week, whenever I saw either of them, our greeting was, ‘Do your worst!’”  From

the top row of

seats, a panoramic view of Shea's. © photo by

Steven D. Desmond

Special thanks to Sue Haefner, Celine Krzan and Kevin Sweeney for their contributions to this story |

Page by Chuck LaChiusa in 2021

| ...Home Page ...| ..Buffalo Architecture Index...| ..Buffalo History Index... .|....E-Mail ...| ..

web site consulting by ingenious, inc.